|

| Caen. Abbaye aux Dames |

2. Not Just a Big Church: a Building Site

A companion to the website Medieval Writing, concerning itself with medieval handwriting and its cultural setting, now expanded to encompass aspects of medieval heritage and material culture. Tweeting as Hipster Bookfairy . Gradually putting medieval photos on Flickr

|

| Caen. Abbaye aux Dames |

|

| From P. Clemen and W. Ewald 1911 Die Kunstdenkmäler der Stadt Köln. Im Auftrage des Provinzialverbandes der Rheinprovinz und mit Unterstützung der Stadt Köln: Düsseldorf, Vol. 3. |

|

| P. Clemen and W. Ewald 1911 Die Kunstdenkmäler der Stadt Köln. Im Auftrage des Provinzialverbandes der Rheinprovinz und mit Unterstützung der Stadt Köln: Düsseldorf, Vol. 3. |

|

| P. Clemen and W. Ewald 1911 Die Kunstdenkmäler der Stadt Köln. Im Auftrage des Provinzialverbandes der Rheinprovinz und mit Unterstützung der Stadt Köln: Düsseldorf, Vol. 3. |

|

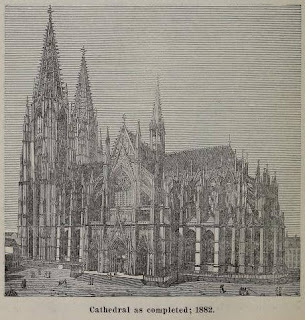

| From F.T. Helmken 1901 The cathedral of Cologne, its history, architecture...legends. A guide for visitors, compiled from historical and descriptive records.. : Cologne. |