The 18th and 19th centuries produced numbers of commemorative monuments to children who had died young, ranging from exquisitely carved monuments to beautiful youngsters depicted as if asleep to sad lists of names, ages and dates on churchyard headstones. These remind us that bringing offspring to adulthood was a perilous exercise in the days when nutrition and medicine were very imperfect and natural hazards were plenty. When you go back to the heyday of medieval effigial monuments, in the 14th and 15th centuries, monuments to dead children are exceedingly rare.

This depiction of a slender young man or boy is even less of a portrait than most funerary monuments. It is dedicated to William de Hatfield, the second son of King Edward III and Queen Philippa of Hainault. He died in 1337 in his first year of life. The alabaster effigy, which lies on a tall table tomb under a vaulted canopy, is very much in the style of a knightly effigy, although he bears no arms. It is as if the depiction of an actual child is something the sculptors just didn't get. It has all the significata of liminality; praying hands, angels and lion foot supporter looking up, but it is hard to imagine an infant having earned too much time in purgatory. Like the far more numerous adult effigies, it is an idealised image of a fine human specimen.

This undersized alabaster tomb in Sheriff Hutton church, Yorkshire, has been identified in the past with Edward, son of King Richard III, who died young in 1484. The tomb is rather the worse for wear and it has been suggested that it may have been moved from the chapel of Sheriff Hutton Castle. It has also been suggested that it is too early in style to be said Edward, but is more likely to be a member of the Neville family (on the basis of heraldry) of the earlier part of the 15th century. It is assumed to represent a young person, as the figure is not in armour or bearing arms, as you might expect of an adult of this social standing.

Effigies which are less than life sized do not necessarily represent children. Smaller depictions have been known to indicate heart burials, that rather odd (to us) medieval ritual whereby a person's heart, or occasionally other innards, was buried in a different place to the rest of the body. This sometimes happened when a person died away from their home or from some place especially dear to them.

This little half effigy of a bishop in Winchester Cathedral is actually holding his heart, which is a clue. He has been identified as Aymer de Valance (d.1261). So size doesn't really matter in this case.

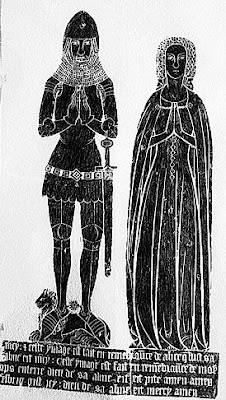

The Roger de Felbrigg of Felbrigg, Norfolk, commemorated on this approximately half sized brass effigy of the late 14th century is not buried here at all as he died in Prussia, as it says on the tomb inscription. This is part of a brass composition to four individuals, only two of whom were buried on the site. Brasses particularly tended to get smaller over time, particularly over the course of the 15th century. Size did matter, but as a signifier of wealth and influence, not of the age of the deceased.

Given this, there is no real reason to assume that small three dimensional effigies, especially quaintly unique little figures, out of context, in out of the way rural places, such as this miniature effigy stuck up on a wall in the parish church of Filey, East Yorkshire, represent children. They may be heart burials, commemorative depictions of somebody buried somewhere else or just modest little efforts produced for folks of less lavish means.

There are occasional depictions on brasses of the late 15th and early 16th centuries of infants who died in childbirth, frequently along with the mother. This tiny brass from Blickling in Norfolk shows a mother with twins, an eventuality which must have increased the perils of childbirth. The newborn state of the babies is signified in these monuments by the fact that they are firmly wrapped in swaddling clothes. The inscription begins with a standard expression "Orate pro anima" (Pray for the soul of ...), which relates to the necessity for prayer to get the soul of the deceased out of purgatory. This is a theme which permeates so much of medieval tomb iconography, even without the specific wording. But, the inscription only asks us to pray for the soul of the mother, not the departed infants who are identified simply as a boy and a girl.

As I keep saying, the concept of purgatory is simply a late medieval Christian formulation for the more general concept of liminality in death. It is necessary to create a space and a time frame for the living to accommodate themselves to a sudden and drastic change of state in their personal lives. Death is just too abrupt. It happens in many and diverse cultures of different religious persuasions. The same applies to birth. There is a pervasive idea that infants who die at birth have not actually made it into the land of the living. In some cultures it was believed that they actually went to a separate place to return when the next pregnancy occurred. The corpses of infants were sometimes treated differently to those of others to indicate that they were not gone forever.

There is a temptation to see something of this in the depiction of newborn infants in swaddling clothes. Perhaps it is a sort of reminder to God (who as we know is a forgetful old duffer who has to be constantly reminded of his obligations in the affairs of humankind) that these little souls didn't quite make it to earth.

Children were often enough depicted on the tombs of their parents, but they weren't depicted as children and they weren't necessarily dead at the time. This 15th century tomb in Burton Agnes church, East Yorkshire, shows a miniature knight in plate armour lying beside the effigy of his mother. This was not a bizarre fashion in infant clothing. The suit of armour was an indicator of his social status. The tiny size does not mean this this is a representation of a dead baby, even one in a symbolic suit of armour. Children depicted on tombs were simply drawn that way; smaller. The weeper figures arranged around the tomb chest are figures of saints, but sometimes representations of the children were used for this purpose.

Photograph from Pratt, Helen Marshall (1914) Westminster Abbey: Its Architecture, History and Monuments: New York via the fabulous Internet Archive.

Children were deployed in this way on the tomb of Edward III in Westminster Abbey, which brings us back to where we started. Originally the tomb had all his multitudinous children arrayed around the chest, but time was no kinder to royal tombs than to others and only six remain, of which the one on the far right is William de Hatfield. The living and the departed children are depicted no differently. They are symbols, but of what? Fertility? Succession? Family obligation to the soul of the deceased? All of the above?

This tiny little brass from Blickling, Norfolk, shows firstly, the prolific reproduction and by inference, sturdy physical robustness of many late medieval women, and secondly, the way that children on brasses were rendered as identical symbols without any form of individuality. They are shown as small, but they are dressed as adults. They do not represent mass family extinction. Just because they were depicted on a tomb does not indicate that they were dead. Perhaps, harking back to the liminality theme, they represent a transition from the family united and alive to the family parted by death, readjusting to a new reality.

The question has to be asked as to how children were commemorated in death. In the absence of physical evidence that is rather hard to answer. Perhaps the deaths of children were regarded as a matter for private grief, not for public display either for religious or social reasons.

Post medieval tombs could depict women who had died in childbirth with their dead babies in their arms, but apart from the little chrysom brasses, this is not found in pre-Reformation tombs, which is one of the reasons the sculpture above, of a woman named as Constantia de Frecheville in the church of Scarcliffe, Derbyshire, is most likely a fake, or at least a mashup of a tomb effigy and an image of the Virgin Mary. Different ages present their sentiments and emotions in different ways.